‘Carbon Dioxide makes coffee taste sour!’ Blooming Nonsense?

A Deep Dive into the ‘Bloom’ - Part 1

We did a lot of research and thinking while developing the Simple Smart Coffee Brewer. Most is related to the Encapsulated Pour-over (EPO) method that it uses. One area that has been of particular importance is the coffee ‘bloom’.

The ‘bloom’ is the preinfusion stage of making pour-over coffee. The normal advice is to add some water to the coffee before you start doing a full extraction. For a very comprehensive account of what is going on during this phase, you can see Section 4.3 of The Physics of Filter Coffee by Jonathan Gagne.

Very briefly, the two main reasons that a bloom is required for traditional pour-over processes are:

Allow the trapped Carbon Dioxide (CO2) gas to escape from the roasted coffee.

Get the coffee uniformly wet.

This article addresses the CO2 release. There is a Part 2 dealing with the wetting issue. For the Simple Smart Coffee Brewer there is no need for a ‘bloom’ and these two articles help to explain why.

There is a third relatively minor issue that was raised by James Hoffman about the impact of water hardness on the bloom, which we also examined and have some thoughts about this, and we will share them in another article.

Carbon Dioxide in Roasted Coffee

When coffee is roasted a lot of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) is produced and much of it is trapped in the cells of the coffee beans.

Overtime the CO2 gradually escapes from the coffee beans and, when they are ground, the degassing process speeds up significantly. When hot water is added the CO2 is forced out of the beans much quicker and very obviously.

Most pour-over techniques recommend a 30 to 45 second bloom – sometimes longer - where a relatively small amount of water (typically twice the weight of the coffee) is poured onto the coffee bed.

After most of the gas has bubbled out of the coffee the main extraction starts, adding the desired amount of water, following one of several techniques.

Various supplementary techniques, including stirring, swirling, pouring in circles, making divots, etc. are recommended to get the desired extraction quality.

So why is it important to get the CO2 out of the coffee? Let’s deal with one reason that is often quoted but, it seems, is completely unfounded.

Blooming Nonsense?

A quick search online can find multiple claims to something like:

“… carbon dioxide has a sour taste. If grounds are not allowed to bloom before brewing, the gas will infuse a sour taste into the coffee.”

Here are three related reasons why this is unlikely.

1. Getting CO2 to dissolve into the water would be a problem.

2. Even if you get CO2 into the water it doesn’t taste of anything. You are breathing out CO2 with every breath you take.

3. Claims that the CO2 forms carbonic acid, which we do actually taste as sour, are at best vague and probably incorrect.

No Proof or Research

Carbon Dioxide Solubility

We’ve not been able to find any reports of research measuring the dissolved or entrained CO2 in brewed pour-over coffee. But it’s probably not a significant amount.

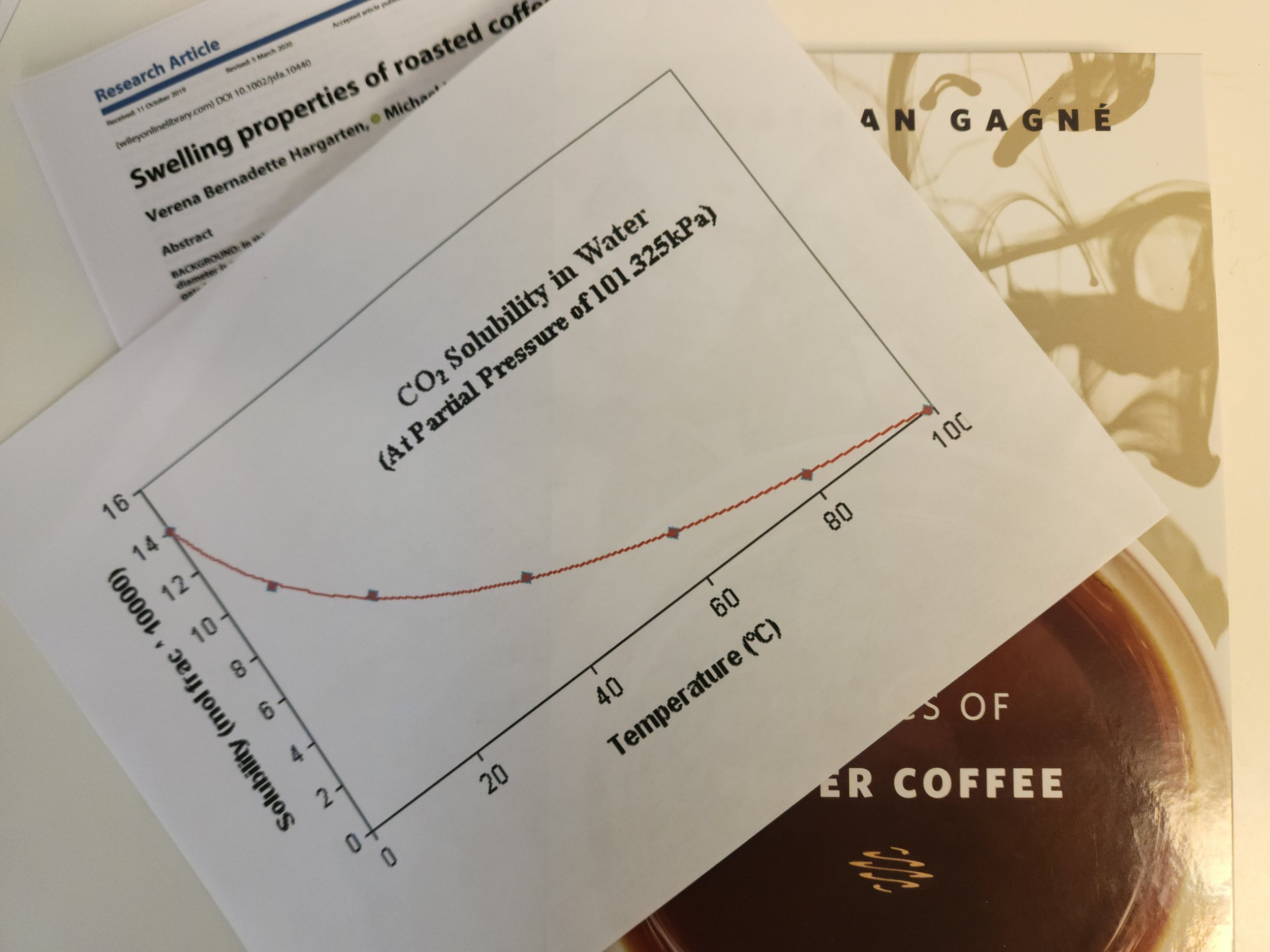

This is because the solubility of CO2 in water decreases with increasing water temperature. In boiling water it is zero. In the ideal brewing temperature range between 195°F and 205°F (90°C to 96°C) the solubility is at, or very close to, zero at normal atmospheric pressure.

‘But it’s not zero!’, some might say. So, maybe there could be some CO2 dissolved in the water.

Even if we grant the claim that there could be tiny amounts of CO2 we still have the issue that it is inert, odorless and tasteless. With every breath we take, we have CO2 in our mouths.

Maybe proponents of the claim that CO2 makes coffee taste sour are thinking about the carbonization of soda, and can retort, ‘Carbonic Acid! H2O and CO2 combine to form H2CO3 … and that is sour tasting.’

That’s true, but at normal atmospheric pressure, carbonic acid in water disassociates to form carbon dioxide and water. That’s why, when you unscrew the lid on a soda bottle, bringing the pressure down to atmospheric pressure, bubbles of carbon dioxide rapidly appear and happily jiggle their way to the surface. In hot water, this is even more pronounced.

Now, these thoughts and doubts do not prove that CO2 doesn’t introduce a sour taste to coffee. As they say, you can’t prove a negative! But for now we have put any such claims aside. We will look at them again if we come across any information that appears to give them some weight.

If anyone has any research about CO2 levels in coffee, we’d love to see it.

How Does CO2 Affect Pour Over Coffee?

Now it‘s true that CO2 can affect the taste of the coffee, but indirectly.

The escaping CO2 has physical impacts, disturbing the coffee bed. As Jonathan Gagne says, “bubbles flowing upward will cause localized channels of much lower hydraulic resistance through which water will flow preferentially, causing further unevenness of extraction.”

Also, the CO2 may prevent water penetration into the cells of the ground coffee – impacting extraction. This seems to be less of an issue than the channeling issue. Some coffee experts have tested this by making pour-over - using good pouring techniques to manage channeling - with and without a bloom phase and the results are far from conclusive. See the video by Keen on Coffee as a good illustration - video.

It is important to have a way for CO2 to be extracted from the coffee bed, but in our testing we have found that the traditional way of creating an unrestricted bloom is probably not the best approach.

Conclusions

You cannot taste CO2 in your coffee because it’s not soluble into hot water, it doesn’t taste of anything, and at normal pressure - and in hot water - carbonic acid cannot form.

But, the CO2 can impact your coffee if it promotes the development of micro-channels as the CO2 bubbles out of it.

As we developed the Encapsulated Pour-over Method, we established an approach that eliminates this issue. The volume of coffee in a contained space expands by about 50% when it is in hot water. The EPO method uses this fact so that the expanding coffee destroys any channel formation by closing them as bubbles form. The expanding coffee simply closes out any channels.

You can see CO2 harmlessly escaping from very freshly medium roasted coffee in a SSC Brewer below (the coffee was roasted one day prior to use here). Normally, medium coffee should have been left to rest for a few days, which allows some of the gas to escape, but we wanted to exaggerate the effect for the video. As each bubble rises up from the stable coffee bed below the filter plate, the coffee expands to fill the void, preventing channel formation.

In the next article about the bloom, we will turn our attention to wetting the coffee.